In the deadwater that is book publishing this month–big publishers have no credit to play with and are offering almost no contracts–an amazing thing happened: the author of a second novel received from Scribner an advance of $4.8 million. Yowze!

Now I could ask if a publisher should bestow a powerful wizard’s wand on only one writer when spreading a few more modest wands around might increase the magic flow for everybody. But I’m not going to ask that. At least not today.

Today I want to focus on how this writer scored her big deal. (Thanks to PubRants for the story.)

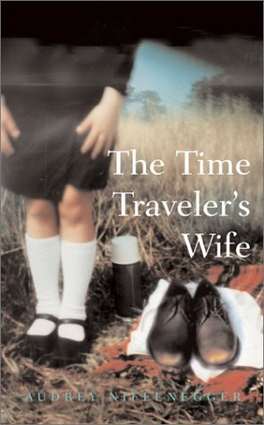

Audrey Niffenegger is a writer and artist whose first novel, The Time Traveler’s Wife (2003) was a huge best-seller. She’s been both a writer and artist since she was a little girl thinking up stories and illustrating them. (My apologies, Audrey, I haven’t yet read your book, but millions of readers gave it rave reviews.)

How long did it take her to write her first book? Niffenegger says,

Four and a half years, all written in the middle of the night, on weekends, and over summer vacations.

In other words, she paid her way with a day job (or two–her bio lists two teaching gigs), and she wrote in her off hours. Artists and writers know how hard it is to stay focused and creative when you’re exhausted from working all day. But she kept at it. And her book was scooped up by book clubs around the country.

All that economic hardship was over when she wrote her second book, right? After all, she had the advance from the first one to live on.

Not so, says her agent, Joe Regal:

In Audrey’s case, she kept her day job for years after publication of TTW; she was careful to live in a way that put the ability to do her work her way, on her schedule, before any other material needs. She protected her priorities.

There’s the magic word: priorities. She kept herself focused on her writing, in spite of the demands of her day jobs, in spite of the distractions that come with teaching. Regal goes on:

That’s discipline, and she had been practicing it on modest means as a visual artist for decades before she became a writer.

Now the word discipline can leave a bad taste in the mouth. It conjures up images of hair shirts or whips, and unless you’re into that kind of thing, you’re likely to stay as far away as possible. It means suffering, deprivation, punishment. It means not enjoying life.

Distaste for discipline is matched only by gagging at goal setting. I for one have a visceral reaction against New Year’s resolutions, and I avoid at all costs the spiritual leaders who make the workshop rounds teaching that if you want to succeed, you’d better set your goals now, and then stick to them or die.

But do discipline and goal setting have to have that teeth-gritting quality–as if life, or our own selves, could be forced into shapes of our choosing?

In Niffenegger’s case, I glimpse a different kind of discipline, a different wellspring for goals. Discipline here is not about setting up a rigid construct or forcing yourself into shape. It’s not about forcing anything at all.

Niffenegger wrote because she wanted to write. She wanted to write more than she wanted a summer vacation or a full night’s sleep. And when you want writing that much, writing is the vacation (though I’ve never found it makes up for a full night’s sleep). She sought writing the way a river seeks the sea–moving forward relentlessly, propelled as if by gravity.

Maybe the image of a river or creek is a good one for fixing our notions of discipline. The first priority of water is to flow downhill, and it will move everything in its path to find the sea. By flowing steadily downward, it carves out a path and then creates banks, which in turn support and ease the water’s journey.

Setting priorities may be like carving out those riverbanks. Whatever we seek with the adamancy of water seeking the sea will set banks beside us, like Niffenegger bringing her material needs into line with her urge to write. Protecting our priorities means flowing within those banks.

It’s just the opposite of going the hard way. Protecting priorities means finding the easiest way down the hill.

And it can pay off. In Audrey’s case, with a $4.8 million magic wand. For most of the rest of us, with the everyday magic of flowing easily, steadily, relentlessly toward that irresistible sea.

Priscilla, I’m hooked on your blog. Every piece I’ve read, including this one, takes me into a truth I feel as both personal and universal. Thanks for your insights, so elegantly articulated.

Hi, Gail, thanks so much for stopping by and letting me know you connect! Updike said it is the job of writers to articulate people’s lives–to help people understand what they are living. I’ve always experienced writing that way–as a service. Hearing that you identify makes my day!