You say you never heard of a local bill of rights?

You’re not alone. I didn’t know much about it either until I attended Democracy School in February.

Ben Price of CELDF teaching Democracy School

Local or community bills of rights are ordinances that spell out certain natural rights of the local community. Like, “We have a right to clean water and air.” Or “We have a right not to have our lands destroyed by fracking.” Community rights bills are legal documents, so they also include a lot of whereases and therefores, but you get the idea. People of a local community come together to agree on a few of their inalienable rights and then state these rights in law.

The people can do this because their state constitutions leave the door open. For example, the Colorado constitution, Article II, Section 28:

The enumeration in this constitution of certain rights shall not be construed to deny, impair, or disparage others retained by the people.

In other words, citizens have rights not spelled out in their constitution, and we the people should feel free to begin enumerating some of those rights. More than 150 local communities across the United States have done just that, the largest one to date being Pittsburgh.

So why are community bills of rights needed?

Because towns and cities are finding that a community rights bill is the surest way to assert control over corporate actions that deface and destroy their local environment.

Other methods have consistently failed. Towns and cities try zoning unwanted corporate activities out of their boundaries, but with very few exceptions, local zoning laws get preempted by the state. Then they try regulating the heck out of environmentally destructive industries, but regulation by definition allows some harm to be done. (If a gas well blows, does it really matter that it’s the regulated 200 feet instead of only 100 feet from your house?)

To a shocking extent, local people do not have the power to decide what happens within their own borders. Corporations almost always get their way.

Most people think this is because of the power of money, but the deeper reason is far more disturbing. Corporations actually have greater power in law than local citizens. The way both federal and state laws are structured gives corporations rights that supersede those of citizens.

Wait, how does that work?

Through a combination of corporate personhood laws and Dillon’s Rule. Let’s take a quick look at each.

1. Corporate personhood laws. Back in the nineteenth century, the Supreme Court began “finding” that corporations deserved the rights guaranteed in the Bill of Rights. The Chief Justice said in an 1886 case (Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad Company),

[t]he Court does not wish to hear arguments on the question whether the provision of the 14th Amendment to the Constitution which forbids a State to deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws, applies to corporations. We are all of the opinion that it does.

Equal protection from then on applied to corporations, not just humans. It makes no sense if you remember that a corporation is a type of property, not a person. But by 1886 the precedent had been set: rights intended for people would be extended to corporations.

Though the Chief Justice’s words did not become part of the written opinion in that case, his position has been upheld by the Supreme Court at least 22 times since then, often explicitly:

1896: it is now settled that corporations are persons, within the meaning of the constitutional provisions forbidding the deprivation of property without due process of law…

1898: that corporations are persons within the meaning of this amendment is now settled.

1906: that corporations are, in law, for civil purposes, deemed persons, is unquestionable.

1923: a state has no more power to deny to corporations the equal protection of the law than it has to individual citizens.

1927: [equal protection guarantees] extend to corporate as well as natural persons.

And on and on. You get the picture. Corporate personhood was well established in American law more than a century before Citizens United.

2. Dillon’s Rule. John Dillon was an Iowa judge who in the 1860s and ’70s wrote a lot of influential opinions about how local and state governments are related. Essentially he said that local communities (except for home rule communities) have no rights that the state does not give them and that everything a local municipality decides is subject to state control.

So if a town or city decides to ban a certain corporate activity, such as fracking, within its borders, the state may override that decision.

And states do. See Pennsylvania’s draconian new law, passed in February, which prohibits local communities from banning fracking and even puts a gag rule on physicians forbidding them to tell their patients how their symptoms may be related to fracking.

Dillon’s Rule means that a city or county is like a child in relationship to the state as parent: subject to the state’s ability to preempt every decision.

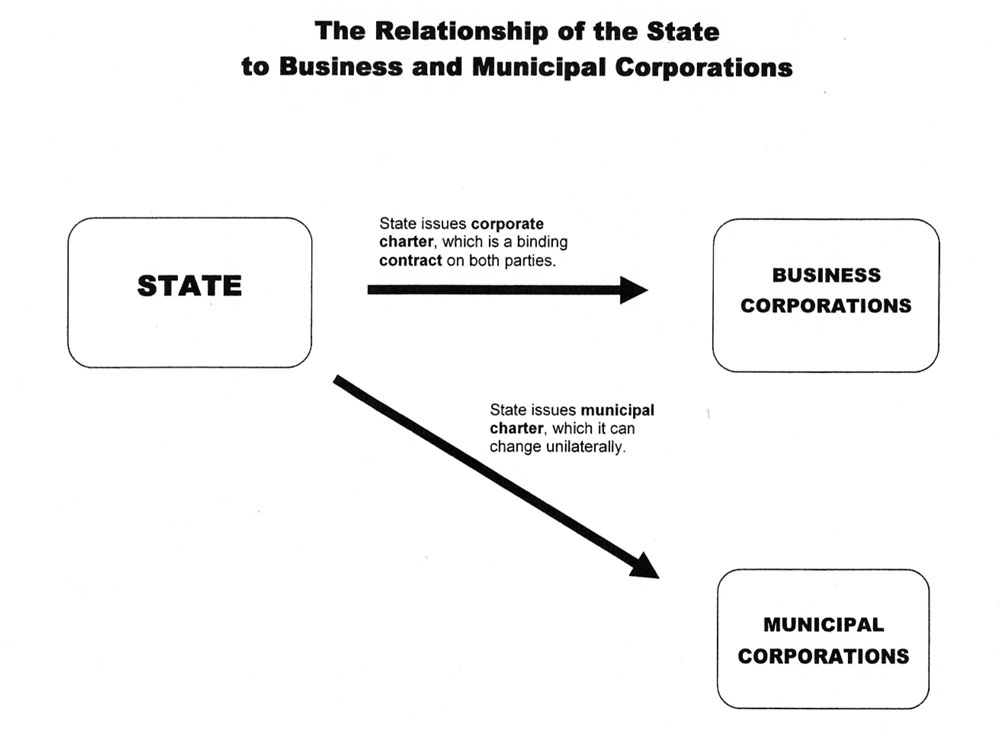

Now what does this mean for towns in relation to private corporations? Well, a corporation too receives its charter from the state. However, the corporate charter is binding on both parties; it takes the agreement of both state and corporation to change it. But the state’s charter to local governments moves in one way only: the state can unilaterally change a municipal charter. This means that corporations by law come out on top:

A corporation can argue that it has a right not to be prevented from engaging in its business (equal protection granted by corporate personhood laws), and by law that “right” will supersede the right of local people to decide what happens within their borders (because the state can preempt local decisions).

So the deeper answer to the question Why do we need a local bill of rights? is: because the right of self-government is at stake. Community bills of rights begin to place local decisions back in the hands of local people.

The civil rights movement of our time is here. And how it plays out will determine not only who gets to make decisions about local lands, but also whether those local lands remain habitable let alone healthy for coming generations.

Next up: Why a community bill of rights needs to be founded on the rights of nature.

Update: On April 2 Las Vegas, New Mexico, became the first city in the Southwest to pass a community bill of rights, using it to ban fracking and protect their water supply and the rights of nature.

To get involved:

- Local groups are working hard to get community bills of rights passed in Boulder City and County and to inform local people of their rights as citizens. Email me, priscilla@thislivelyearth.com, if you want to be part of the movement.

For more information:

- Quotes from Supreme Court decisions come from the curriculum of the Democracy School. Watch the online version here.

- John F. Dillon’s influential book is Municipal Corporations (1872).