Water will win. As we dig out in Boulder from this great flood, we have a new appreciation for the overwhelming power of water. Roads destroyed, lives lost, houses and buildings shoved roughly downhill. Even on my street, on high ground away from creeks, almost every basement filled with several inches—or feet—of water. Throughout the region, water pounded new-old paths downhill; water saturated the ground; water raced to flow into any space it could find.

This week a panel of climatologists and meteorologists gathered at CU to talk about September’s severe flooding. (Listen to the presentation here. The Daily Camera did a story here.) Sponsored by CIRES (Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences) with help from NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) and CSU’s Colorado Climate Center, the panel addressed two big questions:

- How rare was this Boulder flood?

- How much did climate change play a role?

The second question was easier than the first. Yes, said the scientists, climate change does increase water vapor in the atmosphere, but the amount is still very, very small. So:

Climate change did not play a discernible role in the current flood.

More disturbing, said one panelist, is that our historical records are so short. We sit on 150 years of data and “feel smug,” thinking we’ve got the bases covered, when in fact “nature can deliver.” How do we know what average rainfall or flooding intervals were prior to the Industrial Revolution, when we started burning fossil fuels? We don’t.

The panelists’ answer to the first question was more sobering:

This flood was not rare.

It’s been called a 100-year or even a 1,000-year flood, but the downside of using those terms is that we delude ourselves into thinking that a flood like this doesn’t happen very often. In fact, similar flooding has happened in Boulder, not once, not twice, but a handful of times in the last hundred years alone.

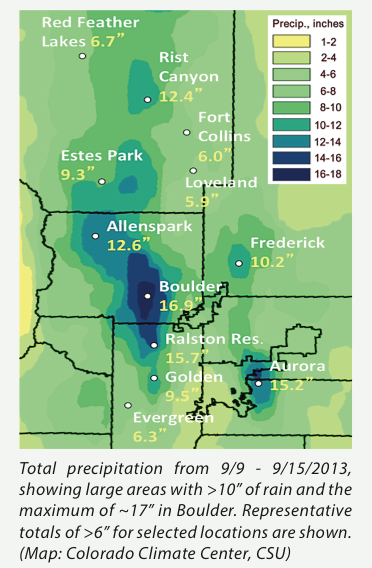

What was rare about this event was the rainfall—fairly slow as deluges go, except for a few brief spikes, but so steady and sustained over so many hours and then days that it amounted to totals previously unheard of. We set records for 1-day, 2-day, and 7-day totals of rain—more than 9″ in 1 day, nearly doubling the old record of 4.8″, and almost 17″ in 7 days, or nearly a year’s worth of rain for this area in one short week. The map of rainfall totals in the area is taken from the report put out by the panelists.

What was rare about this event was the rainfall—fairly slow as deluges go, except for a few brief spikes, but so steady and sustained over so many hours and then days that it amounted to totals previously unheard of. We set records for 1-day, 2-day, and 7-day totals of rain—more than 9″ in 1 day, nearly doubling the old record of 4.8″, and almost 17″ in 7 days, or nearly a year’s worth of rain for this area in one short week. The map of rainfall totals in the area is taken from the report put out by the panelists.

The heavy rains (rather than overflowing creeks) are what caused Boulder basements far from creeks to flood, as the ground simply could not hold that much water. We haven’t yet heard from geologists about this event, but when we do I suspect they will talk about a rock-sold layer of clay that underlies the region a couple feet below the surface—the layer of rock that I’ve heard my gardener and builder friends complain about. Hitting that clay table, the water had no place to go and so flowed into basements.

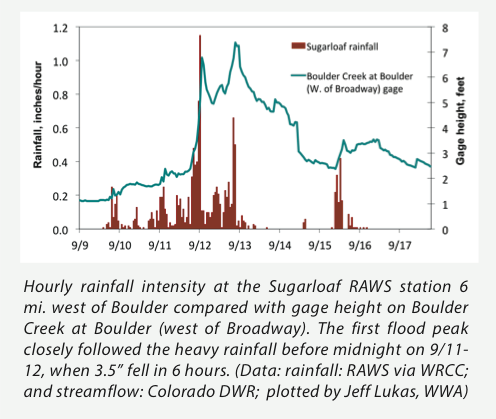

But as for creek flows, they were not extraordinary. During this event, Boulder Creek peaked twice in flood stage. The second time, just after 9:00 pm on Thursday the 12th, creekflows reached 5000 cubic feet per second, or 100 times more water roaring down the creek each second than had been flowing just before the storm.

One astonishing thing to see in this graph is how fast the creek approached flood stage. Before about 9:00 pm on Sept. 11, the creek level was slowly rising. But within an hour or two at most, its flow shot upward—from “water rising” to “life threatening” in a matter of minutes.

And yet the peak flow on Boulder Creek was not that rare. One of the most sobering sentences from the meteorologists’ report is this simple summary:

The peak flows at many gages and the overall extent of flooding were probably unmatched in at least 35 years.

Only 35 years. Not 100. This means that flooding of this magnitude can be expected several times a century. It happened a few times in the past 100 and will likely do so again.

Which calls into question what Boulder mayor Matt Appelbaum said: “You can’t design your entire sewer storm system for 100-year or greater events. I don’t think it’s feasible or something you’d have the funding to do.” He may be right about the funding, but Boulder residents are no doubt going to push for more adequate infrastructure, and have already begun to do so.

Which brings me to reflect on my role in flood recovery. I live near Linden Drive and Spring Valley, where the nearly forgotten Twomile Canyon Creek gushed for days across both roads.

Linden Drive at Wonderland Hill, looking southeast, 8:00 a.m. on Sept 12. A few feet downstream from the first photo.

The creek clearly wanted to go southeast. And the water won. It headed southeast until it piled debris on Broadway at Iris.

A look at the interactive map of the Office of Emergency Management shows why.

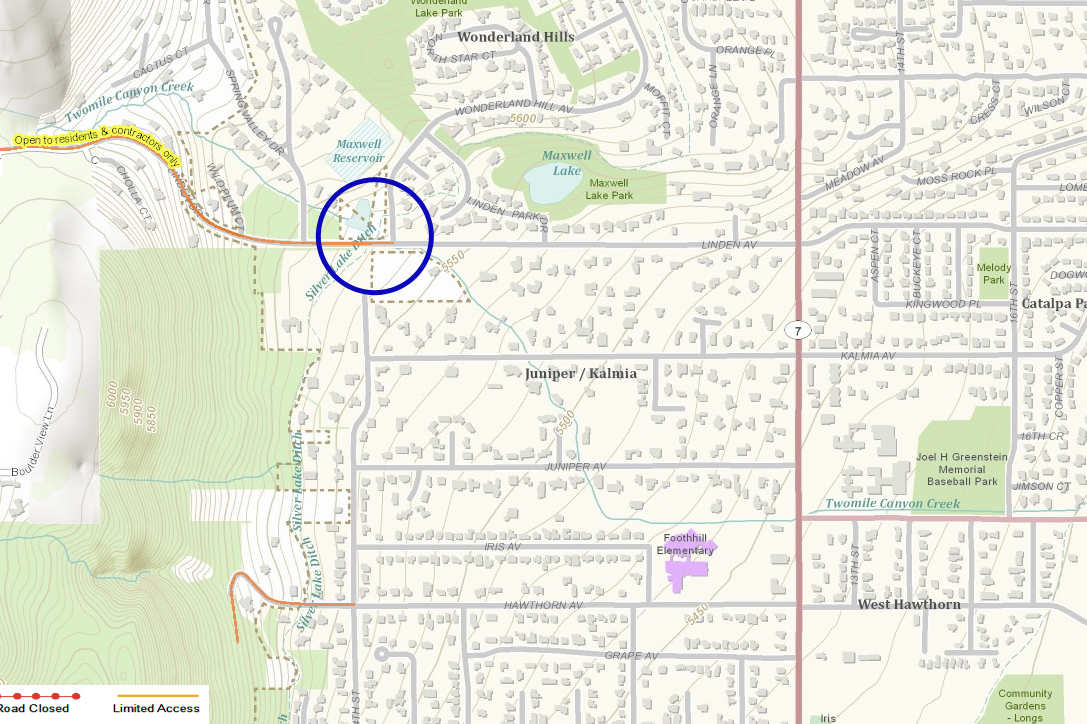

I’ve drawn a circle around the intersection of Wonderland Hill and Linden. Notice the blue creek line flowing to the southeast, arriving at—guess where—Broadway and Iris. This is apparently the historic creekbed of Twomile Canyon Creek.

But look at where Twomile Canyon Creek has been trained to flow instead. This is from the same map, zooming out:

The straight blue line running northeast is a culvert. Twomile Canyon Creek has been diverted from its historic creekbed. In the first map above, look at all the houses in the way of its historic flow. I suspect all those houses experienced massive amounts of water. When Twomile Canyon flooded, the puny culvert at Linden and Wonderland Hill was no match for its engorged flow. Water will win.

You might say that in this part of town, we’re not respecting the flow of water. On Boulder Creek, the shining exemplar creek of our town, water by and large gets to have its say. But on many of the other creeks flowing out of the hills through our town, water has been channelized and culverted. Out-of-sight water has led to complacency in development. Land has been filled in and structures built in the direct historic paths of water.

We forgot water’s power. In the first map, I drew the circle to encompass a little body of water at the intersection of Wonderland Hill and Linden, an overflow pond perhaps eighty feet across and fifteen or twenty feet deep, designed to contain the water so it won’t flood as it enters the culvert. The holding pond sits on one of my dog Bodhi’s favorite walks through the ‘hood. We’ve passed it hundreds of times. Most of the year it is completely empty, a huge depression in the ground. Here is what the raging Twomile Canyon Creek did to that overflow pond:

Filled it solid with rocks and silt carried down from Pinebrook Hills.

Water will win.

And yet there is beauty too in this unusual fall event. I’ve been savoring the greening of the grass, the freshness of the air, as if in September we’re getting the dose of springtime that we missed in April during all that snow. How many times do you get to see fall flowers, like this dotted gayfeather, not surrounded by glowing golden grass as it usually is, but instead bathed in green?

Only after heavy autumn rains.

Only a handful of times in a hundred years.

Update 2015: See this Boulder Camera article for meteorologists’ reassessment of the links to climate change: there was a good chance that the severity of this storm was exacerbated by warmer ocean temperatures and higher amounts of water vapor in the air, both linked to human-caused global warming.