This week the climate data center NOAA released its “State of the Climate: Drought” report showing moisture conditions state by state for the past twelve months. Colorado, as expected after our super-early, dry spring, is in a long-term drought, as is much of the Southwest and southern plains.

But the native plants of the prairie knew what to do with this dry summer: hunker down for the long haul. How did they do it? Here is their strategy.

The patch of big bluestem near my house looked like this a couple of years ago, in October 2010:

Now here is the same patch of big bluestem this year, in October 2012:

What’s missing this year? The tall stems ending in seed heads. Lacking moisture, big bluestem simply decided not to make seeds this summer.

Big bluestem can survive without making seeds because this grass is in it for the long haul. The plant has roots that travel down to forever—at least compared to the grasses we are used to seeing in our lawns and parks and golf courses.

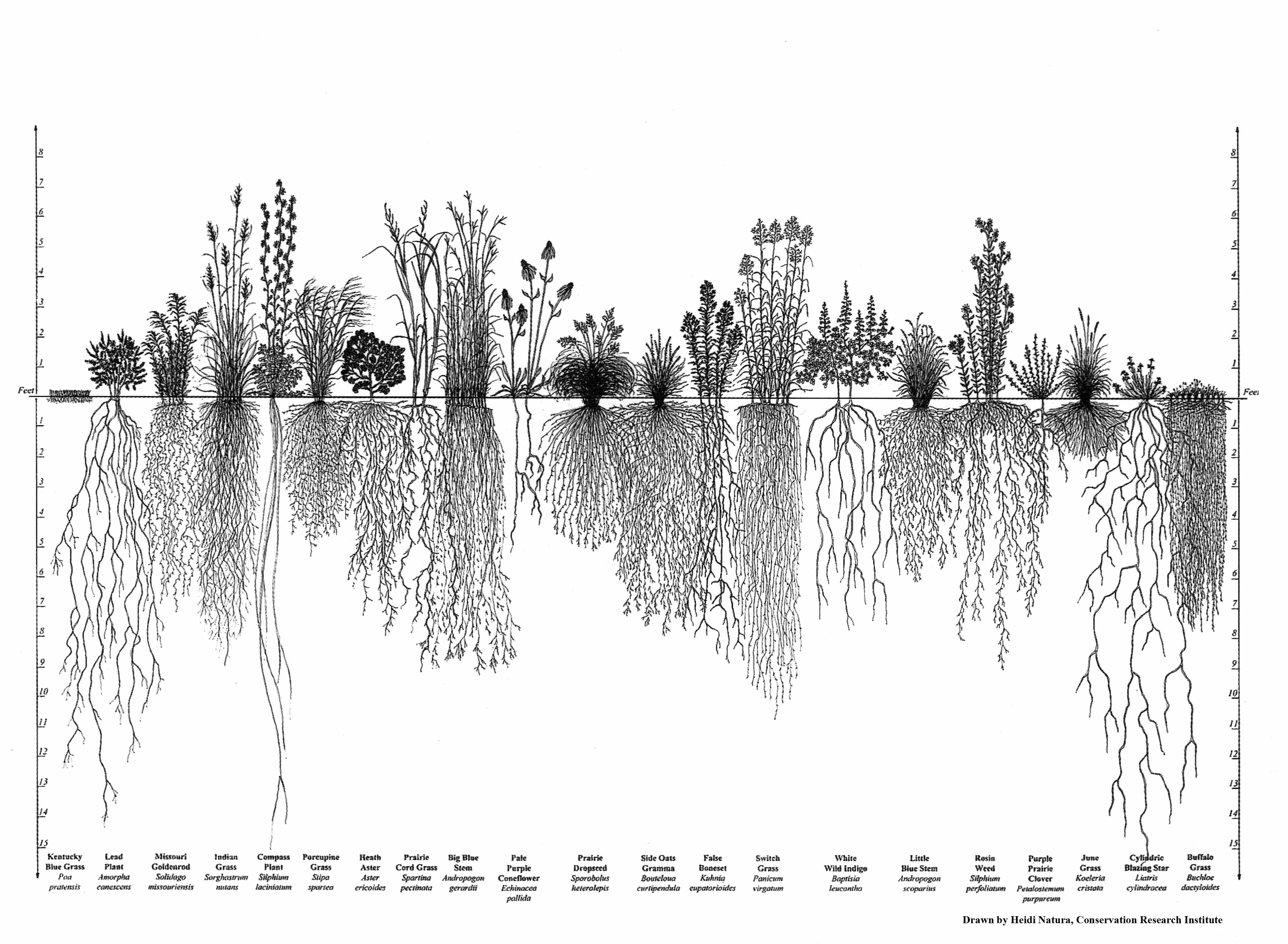

Just how long are big bluestem roots? Take a look at this marvelous illustration, which I found in a book that had nothing to do with prairies:

There’s big bluestem, about a third of the way from the left. Its roots go down not one or two feet but nine feet into the soil. Nine feet! This is the grass that kept the prairie in place for millennia, the grass that was plowed up by European settlers in their frantic rush to plant short-rooted food crops. After the big bluestem and its long-rooted prairie-plant companions had been torn out, the prairie soil was opened to the wind, and the Dust Bowl ensued.

By contrast, look in the diagram at Kentucky bluegrass. This is lawn grass. Having trouble finding it? That’s because on the scale of the prairie, Kentucky blue barely exists. It’s the little toothbrush bristle at the far left with roots only a couple of inches long. Those tiny roots are no match for the strong winds that buffet the prairie plains, the arid conditions at the surface of the ground. To thrive in the windy, sun-baked, fire-seared plains of Colorado, you need deep, deep roots.

In an era of global warming, those long, long roots perform another service as well. Big bluestem has what plant ecologists call high root-to-shoot ratio, meaning that a lot of the plant is underground. And therefore it is especially adept at storing carbon.

I love big bluestem. Not just for its autumn colors, which are splendid, but also for its adaptability. If one year doesn’t work for you, hunker down and wait for the next. Rely on deep roots to carry you through. I love how strong it is, strong enough to hold precious soil in place for hundreds of thousands of years. I love that it could be a strong ally in the climate change we will continue to face.

We need native grasses—especially now. With the increasing likelihood of long-term drought on the high plains, we need the native plants, who know how to thrive in uncertain times. We need their hardiness, their ability to hold and build soil, their carbon storage, their ability to withstand fire.

Consider adding a patch of native grass to your garden or yard. I have seen small bunches of native tallgrass, like big bluestem, decorating the edges of flower beds or gardens. Enjoy the tawny, maroon hues that big bluestem wears in autumn. And take inspiration from its deep roots.