This is part 2 of “Seeking ancestors.” Part 1 is here.

So when I was writing the chapter titled “Ancestors” in Kissed by a Fox, I was inspired to seek out my deep ancestors, the people from thousands of years ago whose genes I carry. Did they, like my recent ancestors, live in Europe? Or did my deep grandmothers and grandfathers have more in common with people in Siberia, Ethiopia, or Chile?

I ordered one DNA testing kit from the Genographic Project (to trace my maternal or mitochondrial DNA) and a second one for my nephew (for the paternal line).

When the results of both tests were posted, I found few surprises: my heritage on both sides is solidly central European. My father’s line is the most common male line in Europe. It is the branch of the human family tree most likely associated with the Indo-European language family and may stretch back to the Proto-Indo-Europeans, a vigorous people with a vigorous language who rode horses and pulled wagons and kept sheep and cows and who moved rapidly and perhaps violently into Europe from Anatolia and the Caucasus 7000 to 10,000 years ago.

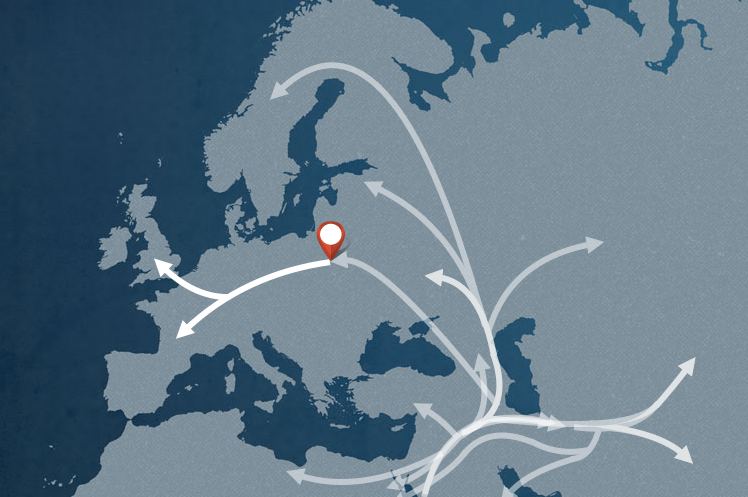

My deep grandmothers migrated into Europe 30,000 or more years ago. From the Genographic Project.

My mother’s mothers, it turned out, were even more deeply indigenous to Europe than that. My motherline goes back to the earliest hunter-gatherers in Europe, living alongside Neanderthals. My deep grandmother, the first woman carrying the genetic mutation of my clade, migrated into Europe from West Asia perhaps 30,000 or more years ago. My ancestral grandmothers, in other words, lived in Europe for a very long time.

Of course, farther back than that—50,000 years or so—we all converge in Africa. My deep-deep grandmothers, like everyone’s, were black. Mitochondrial DNA testing has shown that every human being can trace her maternal line to one African woman who lived around 200,000 years ago. My last African grandmother lived somewhere in East Africa around 50,000 years ago and might have spoken a language that included clicks, a feature of the Koisan language family of African languages and apparently one of the most ancient features of human language.

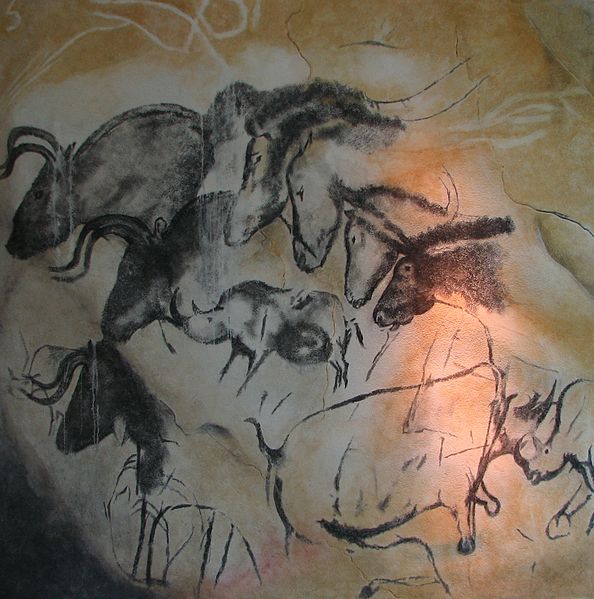

When my deep ancestors arrived in Europe, their languages and lifestyles shifted with the landscape. Living in colder climates, they spent more time “indoors”—in caves. And instead of depicting their relationships with animals on perishable items, such as bark or clay or skins, they began painting on the walls of their homes. And so their art, unlike that of the African ancestors, is available to us on cave walls tens of thousands of years later.

Replica of painting from Chauvet Cave, ca. 30,000 years ago, from Wikipedia

How inspiring, those sweeping lines and sophisticated rendering of horses and bison in the prehistoric cave paintings! Picasso found them so compelling that when he visited France in 1940 to view the cave at Lascaux, painted 17,000 years ago, he is said to have remarked gloomily, “We have invented nothing.”

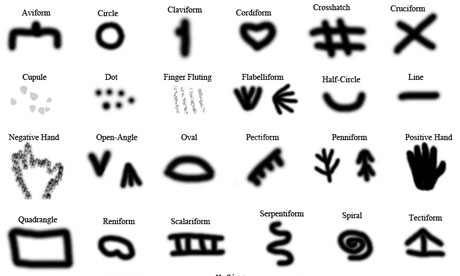

Now, it seems, more than beautiful pictures appear on the walls of the ancient caves. Two researchers from British Columbia, Genevieve von Petzinger and April Nowell, a while back published their findings that the seemingly insignificant marks accompanying the paintings and dating also from tens of thousands of years ago contain recognizable patterns.

The squiggles and triangles and hand shapes appear in recurring groupings from cave to cave. In other words, people wrote them. The marks appear to be the beginnings of symbolic communication. They may show the origins of writing.

The Stone Age people might not have been “prehistoric” at all. They left an intriguing trail thousands of years long of symbols that they apparently used over and over again, most likely to communicate with one another. The honor of dreaming up writing may not belong, after all, to farmers; it may go back tens of thousands of years earlier to hunter-gatherers.

As long as I’ve known about the cave paintings—and especially now that I hear writing may be involved as well—I’ve wanted to see them. Unfortunately for visitors, but fortunately for the caves, they are off limits to visitors. So when director Werner Herzog released his Cave of Forgotten Dreams in 2010, detailing the Chauvet cave in 3-D, I rushed to see it. And was awed all over again by the artistry, the genius, panted on the cave walls. (Herzog ignored the symbolic marks accompanying the pictures, which von Petzinger found a great loss.)

Viewing the movie was as close as I figured I would get to the paintings themselves. Now I hear that, in a manner of speaking, one of the caves tours the world. An exhibition of Lascaux, with scale replicas, will be visiting museums worldwide until 2020. It arrived at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago on March 20 and will be there until September 8. I’m thinking of going.

I’d like to get closer to my ancestors. Especially my deep grandmothers who lived tens of thousands of years ago in Europe. Did they paint their cave walls? I have no idea. I do suspect that women were more likely than men to be the artists, for as one archeologist shows, many of the hand stencils next to the paintings are of women’s hands.

I’d like to know the artists who left their mastery on the ancient cave walls, who experimented with symbols and were the keepers of inspiration. Maybe they were my deep grandmothers.