House chamber of the US Capitol, from Wikipedia

Why is it that the more formal the meeting, the more insulated it is from nature? Think about a courtroom, which typically has no outside windows whatsoever. Or the chambers of Congress or the meeting rooms in hotels–no windows, at least at eye level, to provide a break from ramrod-straight walls and artificial light. All of these rooms are sealed away from earth and sky. It’s as if the more important the deliberations, the harder we work to remove all vestiges of nature from the room.

Now, doesn’t this seem a smidge wrongheaded, given what we know about the effects of nature on the human psyche? Countless studies in recent decades have documented the health-promoting benefits of contact with nature. For a rundown of some of them, see an article in Health Promotion International (2005) from Oxford Press. Contact with nature benefits both mental and physical health, and prolonged insulation from nature shows up in deleterious effects on health.

Never in history have humans spent so little time in physical contact with animals and plants. . . . Already, some research has shown that too much artificial stimulation and an existence spent in purely human environments may cause exhaustion and produce a loss of vitality and health.

Most of us know from our daily experience that even a few minutes of contact with nature help to clear our heads, soothe our spirits, and calm our busy minds. Seasoned hikers may enjoy rain-spattered days as much as sunny ones. A woods on an overcast day is brighter with color than on a sunlit one. Whatever the weather, a walk in a nearby park or open space can refresh or delight. Even pictures of nature promote stress reduction, as many health care givers know, and hospitals these days are finding ways to present nature panoramas for their patients to contemplate.

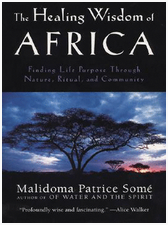

I’ll never forget the book that brought to my attention the Western penchant for insulating itself from nature. It was a manuscript I was asked to develop by Malidoma Somé of West Africa. If we’re lucky, each of us will experience a few moments in life when we sense that we are doing exactly what we came into this world to do, and editing that book was one of those bright moments for me. The book became The Healing Wisdom of Africa: Finding Life Purpose through Nature, Ritual, and Community, a book that Alice Walker called “profoundly wise and fascinating.”

I’ll never forget the book that brought to my attention the Western penchant for insulating itself from nature. It was a manuscript I was asked to develop by Malidoma Somé of West Africa. If we’re lucky, each of us will experience a few moments in life when we sense that we are doing exactly what we came into this world to do, and editing that book was one of those bright moments for me. The book became The Healing Wisdom of Africa: Finding Life Purpose through Nature, Ritual, and Community, a book that Alice Walker called “profoundly wise and fascinating.”

Malidoma’s book brought together nature, spirituality, and community–three values I hold dear–and offered suggestions for Western society drawn from the culture of his people, the Dagara of West Africa. At the time he wrote this book Malidoma held two doctorates from Western universities and had been sent by the elders of his village to teach “village values” in the West. A missionary in reverse, you might say. (He has since been initiated as an elder in his village and continues to spend most of the year living and teaching in the West.)

Malidoma wrote that among his people, the more important the conversation, the more nature must be a part of it. A couple who is experiencing tension in their relationship are advised to take a walk outdoors to sort out their troubles. Youth who are angry–a sign in part that they are searching for their purpose in life–need rituals in nature (what we might call adventure education) to help them know themselves and the world better. A group who seeks to make a decision together should discuss and deliberate while surrounded by nature.

Why? Because nature, being far older than humans, is wiser than we are. We, the children or younger brothers and sisters, have a great deal to learn from its ways–its perseverance (or sustainability), its contrasts and balance, its creativity. Being in contact with earth, wind, and sky, with trees, animals, and clouds, puts us in touch with larger fonts of wisdom than we can access by ourselves.

Every time I walk into a courtroom, church, or chamber I think of Malidoma’s words. What if, instead of sealing ourselves away in stuffy chambers, we opened our most important conversations to the wider wisdom of nature?

I’m sold – your description of Malidoma’s book has grabbed my interest. One of the activities I enjoy the most is simply walking the Niwot loop which runs close to my house. It’s good exercise but more than that, as I walk I look at the mountains and see this great expanse of land. Just being out there gives me a sense of freedom and openness. In that setting I can ponder about the issues that are bothering me and inevitably they don’t seem as big as they do from behind my desk.

Thanks for your comment, Mandy. Isn’t that true–being in nature restores a sense of perspective. I used to visit the ocean for the same reason. I’m looking forward to hearing from more people about their favorite spots.

Perhaps formal, isolated situations have to be thought of as small, self-contained universes. Many were created and formalized when “outside” was generally thought of (Thoreau notwithstanding) as menacing and wild, and interconnectedness was hardly prized.

I’m glad you mentioned that, Claire. I’ve been meaning to do some writing about where Western culture’s idea that “outside” is menacing came from. It is not shared by all cultures, so exploring the history of that idea would no doubt shed some light on our present environmental crisis.

Priscilla, I’m enjoying your blog very much. This post reminds me of when I was working in LoDo and would walk 16th Street Mall every day at lunch. One day I looked down and really saw that the trees along the sidewalks are all caged in a grid; their soil is never warmed by sunlight. And while I was grateful for the trees, I was disconcerted by how controlled nature was in this concrete landscape of high-rise buildings. And by extension, I saw how controlled my work environment was and how that lack of sunlight on my own roots was damaging my health and my spirit.

Thank you for provoking these thoughts and memories.

v