I am caught up in a new adventure, the kind no one ever bargains for.

It began a week ago with a dry and scratchy left eye. Why was it tearing so much? The next morning I awoke to a muscle tic in my lips. Twitch. Twitch-twitch. I pulled out my phone and turned the camera to my face. The left side was not working like the right.

Alarmed, I popped out of bed. Was this my whole face or just one side? Was I having a stroke? I checked arms and legs—fine, at least so far. On the way to the bathroom I grabbed my phone in case I had to dial 9-1-1. (My sweetheart was still sound asleep.) At the mirror I tested face muscles—smiling big, squinching eyes. Definitely less movement on the left.

I paused to see if paralysis was spreading. Arms and legs still fine. It was only affecting my face. It likely wasn’t a stroke.

I was only partly reassured.

A few minutes on Google led me to Bell’s palsy. Affects 40,000 people a year in this country, 1 in 65 in a lifetime. Most likely temporary, though it takes a long time to heal.

The cause? No one knows for sure. For some reason—maybe a virus like the ones that cause shingles and Lyme disease, maybe trauma—the facial nerve on one side becomes inflamed and then dies. Face muscles lose their signals and fall dormant. In most cases the nerve regenerates without treatment and the muscles come back to life. But because nerve tissue grows only a millimeter or two per day, the process can take weeks. Or months.

Over the next couple of days paralysis settled into my face. Eating became harder; so did drinking. Sometimes water dribbled down my chin, other times I choked. Without cheek muscles, forget sucking on a spout or a straw. While chewing, I bit my lip then bit it again. Kissing my sweetheart turned into a lost cause. Or half lost. The left eyelid no longer closed completely, so I needed to blink long and hard, every time. I began propping my cheek in my hand, holding the eye half shut to keep it comfortable.

Luckily my life these days is a quiet one, my work taking place from the comfort of my desk. I could talk to clients on the phone just fine, as long as I worked a little harder to enunciate.

I rested more, finding I often needed an afternoon nap. So much extra work wears you out, you know?

I visited a massage therapist. She placed her hands gently on my scalp, listening. “Did you bump your head recently?” she asked.

Why yes, I did. Two months ago a renegade casserole lid—heavy, glass—slipped off its base while I was placing it on a top shelf. Next thing I knew I had a half-inch gash at my widow’s peak, and the hand that I pressed to it was dripping in blood. (The gash healed fine without stitches.)

“Your suture joint isn’t moving like it should,” the massage therapist offered.

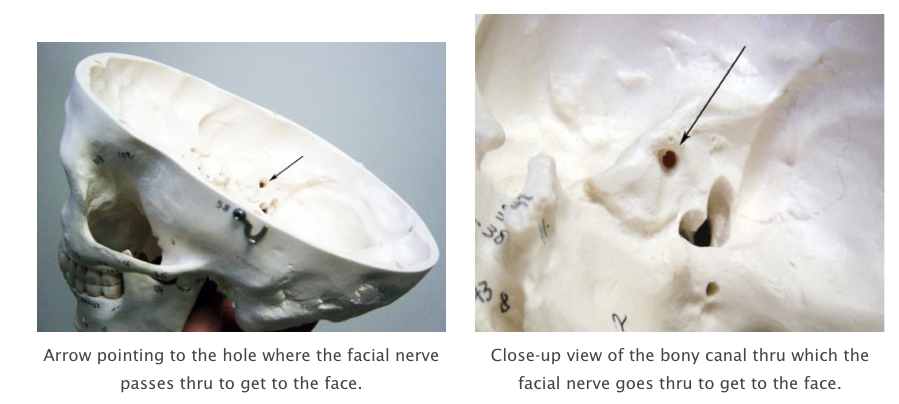

I returned to Google to learn about the skull and the facial nerve. This nerve is one of a dozen cranial nerves, meaning that it originates within the skull in the brain stem, not in the spinal cord. Cranial nerves have to make their way out of the skull, and the facial nerve slips through a tiny hole just below the ear. These photos helped me understand the peril the facial nerve is in if it ever gets inflamed and swells. No room to expand. Damage will be done.

Did the bump on the head displace my cranial bones just enough to put pressure on the facial nerve? I may never know. It’s a good theory, though.

As the days go by, I find myself adjusting. I pay more attention—a lot more—when eating and drinking. A little lip motion has returned, so my mouth can actively kiss my sweetie a wee bit more, though he still encounters limp-fish lips, I’m afraid. Lucky me, he doesn’t seem to mind. After one day of searching out my new face, he adjusted to the changes and didn’t give me a second glance. In a good way, I mean. No extra attention, the unwanted kind.

The bigger adjusting is taking place inside. My sense of loss has deepened as the days go by. One moment I barely notice the impairment; the next I feel like chopping heads. Grief has moved in like an unwashed roommate, one I hadn’t needed to make space for in a while.

I find myself thinking of friends whose bodies were injured. My paraplegic athlete friend who water-skis, bikes, skydives, and beats me at Words with Friends. The photojournalist friend who died of ALS last year, a high-spirited woman who cracked jokes during all the years we watched her lose the ability to move her feet, then her hands and arms, then her eyes. The orchestra conductor in college who, after a surgery near his ear, returned to the podium with slurred speech and a half-working face, his verve for the music undimmed. The cousin across the country who in high school nearly died from a fever that left her muscles jerky, who went on to get married and raise a family, including twin boys, and is now enjoying her grandchildren.

I find myself sending a silent thanks to each one—for dealing with what life handed them. For adjusting to what is possible. For enjoying their life whatever shape it took. It is a powerful thing to watch someone enjoy life—and I am grateful to each one for finding the equanimity to do that. I imagine it took some work.

I send each of them a thank-you especially for being themselves no matter what. Because a deeper layer here is how I see myself, and how others see me. Getting your face moved around without your permission is, at best, unnerving. (Literally true this time!) Now I hesitate a bit before going out in public—and I have some very public events coming up soon, like a radio interview and a book reading. Will I be brave enough to do them? Will I have the energy? I guess we’ll find out.

A spiritual path has a lot to say about becoming disfigured, even temporarily. My own path is teaching me about looking below the surface for what’s real instead of stopping at appearances. In a meditative journey this week one Spirit Helper observed that modern culture, unlike more Spirit-centered cultures of the past, looks almost entirely on the surface of things, prioritizing how people look, and that one gift of this facial challenge is that I, who can get caught up in that tendency (it was clearly said) am being invited to rearrange my priorities and live a freer life. The words were offered gently, but I got the point. (Concerned about appearances—what, who, me?) This same wise friend added that anytime priorities get rearranged, feelings of grief will arise.

My spiritual path has provided comfort too. The day I came down with this malady, but before I knew it was happening, in a meditative journey I was shown the joy that bubbles into physical reality out of its mysterious, hidden source. From the tiniest plants in the garden to the body of each person to every point in outer space, reality boils over with rollicking, roiling joy; each body is its visible presence, each of us its outgrowth. Joy is the switch that turns us on at the start, joy the fuel that grows us, and joy the creative fingers that stitch together all wounds, from the scar in the tree bark to the intricate human heart.

It was a marvelous picture, and I have returned to it time and again this week. I believe it was given for that purpose. When feelings of sadness and loss arrive, I attend to them, and they pass. And when they pass I root myself again in growing things; I see again their source in irrepressible joy.

This is, after all, how nature heals—by offering its flow of unstoppable creativity, its endless gleeful variety, its untamed urge to generate and grow.

I suspect the closer I live to this source, the more easily a facial nerve will regenerate.

Oh, and it doesn’t hurt to know that George Clooney had Bell’s palsy once. For nine months. In ninth grade, poor guy.