I am always curious about my ancestors, even though I often find myself wishing that the ancestors of Western cultures had given all of us a different set of Earth values—more appreciation for the web of Earth-life, more emphasis on loving other beings than on using them. So, when I was writing the “Ancestors” chapter in Kissed by a Fox I was inspired to have my DNA tested. Where did my ancestors come from long, long ago?

I am always curious about my ancestors, even though I often find myself wishing that the ancestors of Western cultures had given all of us a different set of Earth values—more appreciation for the web of Earth-life, more emphasis on loving other beings than on using them. So, when I was writing the “Ancestors” chapter in Kissed by a Fox I was inspired to have my DNA tested. Where did my ancestors come from long, long ago?

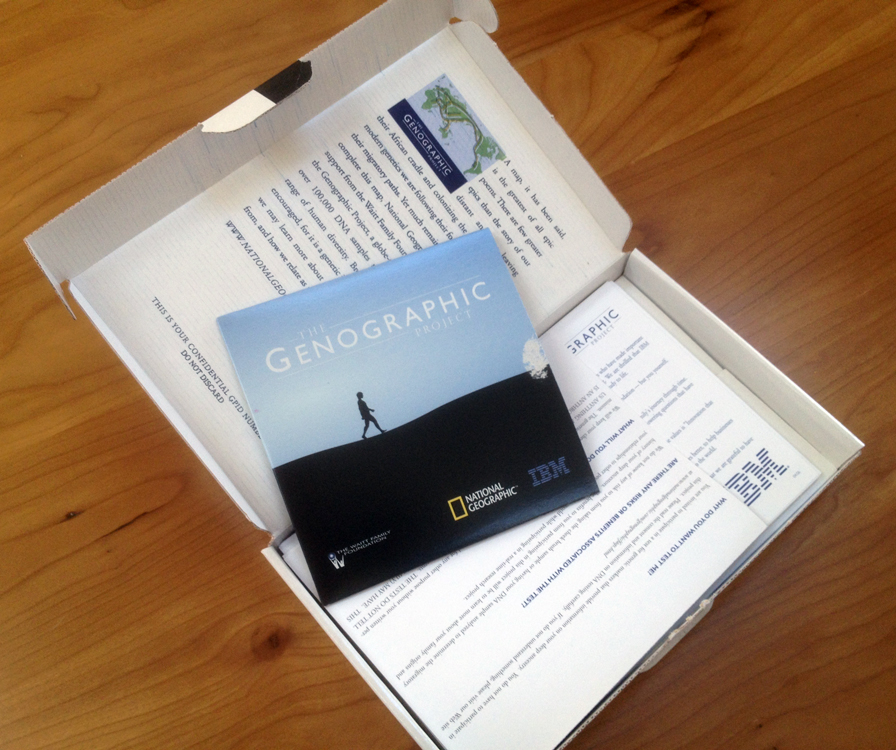

I picked the Genographic Project by National Geographic and ordered my cheek swab to trace my maternal line. I ordered a second kit for my nephew, my brother’s son, to trace our paternal line. (Women can ask their father or his son or grandson to perform the test.)

Now, I’m more than usually acquainted with my more recent ancestors. I know they came from central Europe. I even have a name or two from a family branch stretching back to the 1500s in Switzerland. I know this because I was raised Mennonite, and Mennonites care about genealogy. They also care about the fact that during the Protestant Reformation of the 1500s, our ancestors who later morphed into Mennonites and Amish were the dissenters called Anabaptists. These Anabaptists were generally peaceful people, refusing to bear arms because they believed no Christian should engage in violent coercion, and refusing to baptize their infants for a similar reason—because people should make decisions of faith on their own, not because of having been coerced into it as infants. Anabaptists, and the Mennonites who followed them, placed a high value on individual choice.

They cared about individual conscience so much that Anabaptists of the 1500s gathered in secret enclaves to do something very radical: in an age when baptizing infants made them members of both church and community, they rebaptized one another as adults. Rebaptizing amounted to declaring existing church authorities invalid. And because those church authorities were identical with town and state authorities, Anabaptists got into deep trouble. Their sedition landed them in jail cells, on whipping blocks, and at the bottoms of rivers, shackled to rocks.

Mennonites know these stories because of an enormous tome from 1685 called the Martyrs’ Mirror filled with horror stories of beatings and drownings and stake burnings. The Martyrs’ Mirror is historically one of the most important books among Mennonites, handed down through generations. When Amish and Mennonite peasant families crossed the ocean to North America, the only books they were likely to carry, if they carried any at all, were the Bible and the Martyrs’ Mirror.

Many Mennonites during my lifetime lost interest in the Martyrs’ Mirror, no doubt because it was a reminder of a disturbing and traumatic past that we often preferred to forget. We had mixed feelings about taking our identity from historical persecution. The only Martyrs’ Mirror I ever saw in the Mennonite community where I grew up was the one I, a nine- or ten-year-old voracious reader, occasionally hauled down from its spot on the shelf in my favorite room in the church, the library. The book was large, thick, heavy, horrifying, its bold medieval script matching the heavy starkness of its etchings.

(For a splendid recent essay from the Paris Review on the Martyrs’ Mirror and on why, when you’ve cut your literary teeth on its passions, the popular Amish romance novels seem rather wimpy, go here. Thanks to Andrew Sullivan for the tipoff.)

These martyred Anabaptist ancestors were familiar; until recent decades they practically occupied the spare bedrooms of Mennonite houses. We were used to them, and though we had mixed feelings about the history itself, we were proud of how they had behaved, refusing to be swayed by bullying from church or state. The martyrs had courage and more than the average stubbornness. (Which is saying something if you’ve grown up Mennonite.) We preserved their names as heroines and heroes. And yet, in preserving their stories, we preserved as well a history of trauma, reinforcing for each new generation a sense of separation between “us,” the persecuted minority, and “them,” the mainstream culture, a separation that during times of war was renewed by the suspicion and sometimes abuse suffered by conscientious objectors.

This five-hundred-year-old story of trauma, by the way, underwent a dramatic shift toward peacemaking in 2003 when churches in Switzerland hosted a conference on reconciliation, inviting North American representatives of the groups whose ancestors had been persecuted. At the conference Swiss local officials acknowledged the wrongs done to Anabaptists and asked forgiveness for inflicting torture and execution. A step toward healing was taken in the only way historical trauma can be healed, by speaking the truth of old stories, asking forgiveness, and choosing reconciliation.

So when I ordered my cheek swabs from the Genographic Project, my relationship with my ancestors was already complex, tinged by old stories of trauma, complicated by revulsion as well as respect. I was used to thinking about those martyrs whose lives and stubborn faith stretched back five hundred years before my own. But what I wasn’t used to thinking about were the people who came before those radical dissenters. For how many generations, how many centuries, before 1500 did they too live in central Europe? Where did they come from in the deep history? It was time to find out.

I followed the kit’s instructions and mailed in my test, and my nephew did his test as well (for the paternal line). Then I waited impatiently for the results. Did my deeper ancestors too have their roots in Europe? Or did strands of humanity unimagined flow through our veins?

Part 2 of “Seeking ancestors” appears in the next blog post.