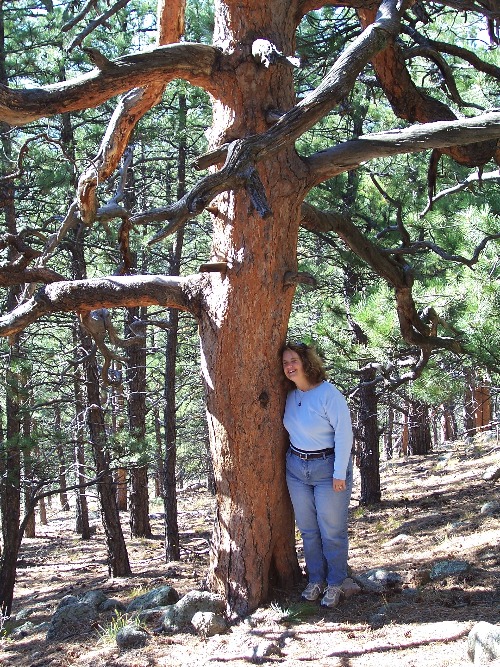

While the Fourmile Fire was still burning, I started hunting through my photos. The fire was advancing toward—maybe had already passed through—Bald Mountain. Where were my photos of the ancient tree on its western slope? Just the day before the fire started (September 5), I’d hiked to the tree, feeling its smooth-rough bark and sniffing its aroma of butterscotch.

Photo by Barbara Voss, Betty Taylor, Priscilla Stuckey

The ponderosa pine was old—eight hundred years old, said one naturalist. If true, the tree was a sapling while across the state the cliff dwellings of Mesa Verde were being built by Ancestral Puebloans, and across the ocean Francis of Assissi was wandering the hills of Umbria.

What wisdom accumulates in the tissues of a tree that old? I felt awe every time I stopped next to its sturdy thick trunk, its craggy branches twisted this way and that through centuries of wind and fire.

Photo by Barbara Voss

Flexibility. Bending to wind. Sending roots deep. And of course its own ancestral wisdom, buried deep in what modern humans call its genetic code: the ponderosa pine’s ability to withstand fire.

A ponderosa forest, left to itself, works like this: young trees sprout, too thickly for the forest to sustain over time. Some need to be weeded out. Along comes fire every dozen years or so—fires of low intensity because the brush on the ground has accumulated for only a few years. The fires stimulate new plant and wildflower growth, taking out the trees too young to protect themselves and sending their nutrients, by way of more nitrogen in the soil, to the older, more established trees.

When fire passes through, the old trees know just what to do. Their bark is thick, insulating their delicate, juice-transporting inner cambium from the wildfire’s fierce heat. So they stand like torches while fire races up their trunks and devours their needles in a crackling blaze of fireworks. There is some evidence that even high-intensity fires do not harm the older trees. After being blackened by fire, their shells come to life again, sprouting new green needles along roasted limbs.

Which is why, when I hiked up to Bald Mountain last week, a month after the Fourmile Fire, I was shocked to see the old tree sawed to the ground.

I email Boulder County Open Space asking why. A polite official emails back:

I email Boulder County Open Space asking why. A polite official emails back:

That tree (as well as several others in the immediate area) was cut down by our forestry crew because it posed a threat to trail users since it was only a few feet away from the trail.

It is a policy of course I disagree with—a litigious society turning our public officials overprotective because a few people, through lawsuits, can hold others responsible for their own dubious choices. Besides, the tree was felled with its trunk toward the trail, and enormous as that trunk was, it still did not reach the trail.

While I am gazing at the sawed-off tree, I can’t escape the feeling that it is the chainsaw, not the fire, that killed it.

As far as I know, immediately after a fire there are no clear signs that a ponderosa is truly dead. Only time can finish that story. But time was not allowed to pass. We ended the tree’s reign, likely before the tree itself chose to do so.

And here’s the odd thing: in the presence of the tree, I find it impossible to feel sad.

I wander among its charred ruins snapping photos. In its center, some other lover of its life has already left an offering of white flowers:

Yes, the heart of the tree was gone. But this, I learn with a bit of reading, is not unusual for old ponderosas. Scarred innumerable times by fire, they form arches at the bases of their trunks where the bark has grown around burned cambium. As far back as the 1940s foresters were calling these “cat faces.”

The tree’s twisted limbs form fantastic shapes, as gnarled in death as they were in life:

And still its bark is stunning—blackened now but charged with a metallic sheen, like the most highly prized blackware pottery of the Southwest:

Up close, I see that the bark damage is only superficial. Even the outer layers are intact, their unique ponderosa patterns still perfectly etched upon the surface:

Up close, I see that the bark damage is only superficial. Even the outer layers are intact, their unique ponderosa patterns still perfectly etched upon the surface:

The fire on this side of the hill was intense. And yet the damage to the bark was minimal. I am amazed at this tree’s resilience. What a blazing torch it must have presented to the sky as the fire passed through!

The fire on this side of the hill was intense. And yet the damage to the bark was minimal. I am amazed at this tree’s resilience. What a blazing torch it must have presented to the sky as the fire passed through!

I can’t stop gazing at the downed tree. Here, a play of light and dark along a burned-out limb:

Finally I tear myself away and head for home. Still I find it hard to feel sad about the tree. Is it the denial stage of grief, which often blunts the first news of loss?

Finally I tear myself away and head for home. Still I find it hard to feel sad about the tree. Is it the denial stage of grief, which often blunts the first news of loss?

Or is the denial stage itself something more than just denial—some certainty, born in our own resilient cells, that life continues into life, that nothing living is ever truly lost?

Of course the certainty does not last, and later the crying catches up with me, deep heaving sobs—

For the loss of this tree, for the current of life that flowed up its trunk, a current palpable to the touch.

For the act of the crew that cut it down, a tree story ended probably before its time.

For the mounds of ash just down the hill from this tree, each mound once a house sheltering generations of stories.

For my friend whose lifetime of keepsakes is now one of those ashen mounds.

For the sound of the helicopter tankers during the fire, whose hammering was so loud over my neighborhood—next to the life-giving lake—that every time one passed overhead, every ten minutes, the birds scattered in fright, the dogs cowered, and the houses quivered on their foundations.

For how strong and fragile and beautiful this tree’s life was. And all our lives are.

In the end, I email friends for pictures of the tree when it was alive. In my own files I can’t find a single one. A graphic designer helps me Photoshop a human out of the best shot. Even in death, the tree is working magic; it takes a small village to preserve its memory.

I think this tree’s story is not yet over. I want to find out more about its life, and the policies that led to its death—from fire suppression, which intensifies a burn, to the decision to cut this tree down. I will be contacting county commissioners and naturalists and anyone else who can fill in a piece of the story.

For more information:

- A 1940s article in the Journal of Forestry when ponderosa forest ecology was new to European-Americans.

- A study by a CU student of Boulder County ponderosa pines after fire.

- On the fire ecology of ponderosa pines.

- History and photos of ponderosa pines.

These are stunningly powerful photos of the ponderosa–now I’m in love with it too! Thank you. We walked through burned forests on the Pacific Crest Trail, and came to love their deep silence, tiny signs of life, and most of all profound reminder of the cycles of nature.

The nature writer and philosopher Kathleen Dean Moore writes of a forest fire that devastated an ecosystem she loved next to a lake. She stood beside the lake, between charred forest and blue water, and asked, “What is this world, that life and death can merge so perfectly that even though I search at the edge of water, I can’t find the place where death ends and life begins?” (Pine Island Paradox, 162)

Wonderful post, Priscilla. Your response to this tree’s death is loving and respectful. I am increasingly seeing dead trees in the mountains: pines from the pine beetle, and aspens from drought and other unknown causes. The hardest for me to bear are seeing the bristlecone pines dead, because they are thousands of years old, and I have witnessed their deaths in the last 20 to 30 years. It breaks my heart.

Yes, it is heartbreaking. And yet the way of the forest is change–through fire especially. And if the forest isn’t allowed to burn, the forest will figure out other ways to survive, thinning itself with pine beetles. Do you know the causes of the bristlecone deaths?

stunning beauty and resiliance…even in the midst of devestation and death. inspiration enough for a lifetime!

Annette, I know from your experiences of loss that you do not say this lightly. Thank you.

Thank you very much for this post. I am so sorry they cut this tree down. I have one of the oldest Ponderosas in Lefthand in my yard, according to one of the Boulder County foresters. It’s been fighting for its life ever since a big drought year about 8 years ago, but it hasn’t given up yet. It’s interesting to me that Boulder County has taken a protective interest in my tree and yet went out of its way to cut the tree you describe down.

I’m moved by the person who left the flowers.

How old is your ponderosa, Claudia?

I found those flowers moving too. What a sweet way to show their connection to the tree, the land.

Priscilla – Thank you so much for sharing this beautiful but sad story. Maybe, just maybe, a sprout will grow from the ashes, if the root structure can muster it up. Here’s hoping.

Yes, I hope so too. Or if not, this tree lives on in its progeny all over the hillside. So many seeds in 800 years!

This was so sad to read. Thank you for a wonderful story.

Priscilla,

Thank you for writing about your love for this tree. I remember it well–the feminine, skyward reach of branches; the mosaic of bark; the fire scar on its uphill side.

Brings me sorrow to know that it got so fried in the fire. A human-caused fire like that burns so hot…

And a jarring ending to its story, to chop it down.

We’ll try to dig up some photos too and send them along. My spouse, who is a dendrochronologist, will likely add a comment here soon.

Thanks again for honoring this spirited tree.

Christine, thanks for the offer of photos. I’ll be happy to post them in an update. Yes, the fires now are hotter because humans are living in the forest and not allowing the forest to burn when it needs to. That could be helped by selective clearing of properties, to simulate a low-intensity burn. I was cheered, though, to find that ponderosas may be able to survive even high-intensity fires.

Priscilla: I was deeply moved by your story. I cannot imagine how this could have happened. How could people who work in the forest not care about the life of this magnificent tree? I will look forward to what you find out. In the meantime, you have given the tree and beautiful tribute that made me aware of its incredible life. Thank you.

Pattie

I suspect that they felt they had to care more about fear of injuries to the public—and lawsuits. I think it’s worth registering our disagreement with the policy, in letters or phone calls. We’re the public too.

Priscilla,

Thank you so much for making us so aware of the depth of what happened up there and to that tree specifically. I can’t help but wonder what kind of education is involved with the people who clear the forests after a fire like this. Perhaps there is a gap in knowledge about the life of a giant old tree like this in relation to fire, and it seems that there could be other ways of addressing the fear involved in the decision to cut this magnificent life short. Ignorance can run deep, and it seems this might have played into this tragic decision. It’s done now, and honoring the tree as you have (and the flower bearer), allows it to live on in our hearts. Thank you for that.

Thanks for your comment, Catherine. Yes, let’s look for ways to address that fear. I am trying to get a better idea from the folks at Boulder County Parks and Open Space why they decided to cut the tree down. They did a good job of thinning the ponderosas on the hillside last year–which kept the fire at a lower intensity in the thinned zones. But why they would cut an obviously well loved giant old tree, as well as clear as much of the hillside of burned trees as they have–these are questions that still need some responses.

Hi Priscilla-

Thanks for your tribute to an old friend. I first met this wonderful pine in the early 1990s, and visited it often when I lived in Boulder. As a dendrochronologist (tree-ring scientist), I also had a professional interest in this tree’s story. In 2003, for a project to reconstruct the history of drought in the Boulder Creek watershed, I cored this tree and about 20 others on Bald Mountain and developed a site chronology that went back to 1683. This particular tree, as you know, was much older than that (my best guess is that it germinated in the 1400s), but I learned in coring it what is clear from your photos: much of the heartwood had rotted out, leaving a thin shell of solid wood to support the tree. Nonetheless, that thin shell had 270 rings, with an inside date of 1733. It was growing very, very slowly in the last 50 years, but it was hanging in there, until the fire.

I’m uncomfortable with the speculation/presumption that the county forestry crew caused the death of the tree by cutting it down. From your photos, it looks like most or all of the crown (the live foliage) was consumed in the fire–which would have killed the tree. Did you see intact needles on any of the branches? Ponderosa are very fire-resistant, as you noted, and can survive multiple surface fires and even scorching of most of the crown (i.e., needles turn orange from the heat but are not consumed). But when the needles are consumed by fire, the underlying buds are burned, and ponderosa pines can’t regrow their needles if the buds are burned.

My guess is that the forestry crew recognized this, and cut it down believing–correctly, I think–that the tree had suffered damage that it couldn’t survive. (Whether they should have left it standing, given the distance to the trail, is a separate question.) I will try to get up to Bald Mountain soon and look for myself, and pay my respects.

Thanks for dropping by, Jeff. This is great information. I hope you’re right–that the forestry crew assessed accurately that the tree couldn’t survive. Germinated in the 1400s–a life of 600 years is pretty grand! I feel awestruck at witnessing the death of a being that old. Yes, definitely worth paying respects. Thanks again for filling us in on some of the facts.

It’s mind-boggling to think of that tree as a sapling in the 1400s. How amazing that we’re constantly surrounded by such ancient grandeur–whether in the form of trees or rocks–and yet we’re seldom even conscious of it. How many animals and birds have lived and died under that tree’s canopy? How many people, heavy-hearted from loss–of a home through fire, of a relationship that failed to thrive, of a loved one stricken by illness or an accident–have felt some comfort from that tree’s singular and powerful presence? When we think of our own lives within the context of such a tree, sorrows heal and petty annoyances evaporate. Thanks!

Beautifully said, Laurel. In some ways that elder tree had a similar effect on me as standing by the ocean, for exactly the reason you express so eloquently: a reminder that my life and my troubles are small in the grand scheme of things. The petty things drop away, as you said. And it was always a reminder of how tenacious life is. I always felt more peaceful after visiting the mountain, and more resilient and hopeful after saying hello to the tree.

Priscilla, I certainly hadn’t thought of the trees in this area being around for 800 years. I assumed they were all second growth. That tree looks like it could have survived, but what Jeff said seems to contradict that. I too would have preferred giving the tree a little more time.

Beth, there are very few because of the intentional burning in the late nineteenth century during the mining era, which you no doubt already know about. But because mature ponderosas can survive fires, this one apparently did. It seems this one was 600 (not 800 as I first thought). Still, 600 is pretty impressive. I still think the county was being a little too proactive–this tree was far enough off the trail and didn’t need to be cut for public safety.