Note from Priscilla: This is my third post from Rio.

Early light seeps through the gap in the blackout curtains in this little rental apartment two blocks from Ipanema Beach. The predawn lightning and thunder have moved on, and today, like yesterday, promises to be cloudy and humid, 75 comfortable degrees in the dead of winter in Rio.

Early light seeps through the gap in the blackout curtains in this little rental apartment two blocks from Ipanema Beach. The predawn lightning and thunder have moved on, and today, like yesterday, promises to be cloudy and humid, 75 comfortable degrees in the dead of winter in Rio.

Heading out to catch the shuttle bus, I stop at the juice bar on the corner. Two dozen smoothie combos to choose from, plus sandwiches. This morning I try something new—açai with granola. It’s a thick slushy of açai berries dark as chocolate—tons of vitamins in my breakfast.

The conference center is an hour away, and to get to the bus stop at a beachfront hotel I run a gauntlet of parked black limos, red-bereted soldiers in camouflage, and motorcycle police with sirens screeching. Usually the bus wait is 30 to 45 minutes. Today I am lucky, and the bus arrives immediately.

On the bus I hear languages of the world. Behind me is a man with an Indian accent. Ahead, African men argue excitedly in French. I recall previous rides. One night a Brazilian high school girl fluent in three languages gave me a Portuguese lesson, and last night I gave a writing lesson to a white-haired man from Rio who spends half the year in Vienna. When he heard me describe my soon-to-be-published book, he asked, “What is creative writing?” We talked about using sensory details, about writing for beauty, about adding emotion and putting yourself in the story. “Ah!” he said, his face lighting up. “I am often asked to contribute a column to a paper. Next time I will show myself drinking coffee. I love coffee!”

At Rio Centro the conference pavilions smell of freshly laid plywood, and the floors spring slightly with each step.

My schedule will start a little later, so for now I stop in at the plenary overflow room to check out the official proceedings on the large screen.

My schedule will start a little later, so for now I stop in at the plenary overflow room to check out the official proceedings on the large screen.

The proceedings are depressing. On this almost everyone here agrees. Instead of a document with detailed commitments to reduce fossil fuel emissions—what people all over the world fervently hope for—the Summit text has been watered down, hijacked by the fossil fuel industry, say most. Instead of focusing on renewable energies, the text includes fossil fuels too. The heads of state are endorsing it. Protests have begun.

The proceedings are depressing. On this almost everyone here agrees. Instead of a document with detailed commitments to reduce fossil fuel emissions—what people all over the world fervently hope for—the Summit text has been watered down, hijacked by the fossil fuel industry, say most. Instead of focusing on renewable energies, the text includes fossil fuels too. The heads of state are endorsing it. Protests have begun.

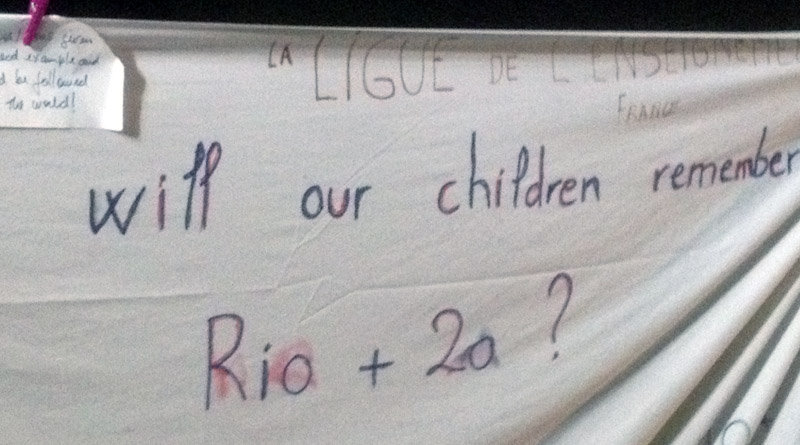

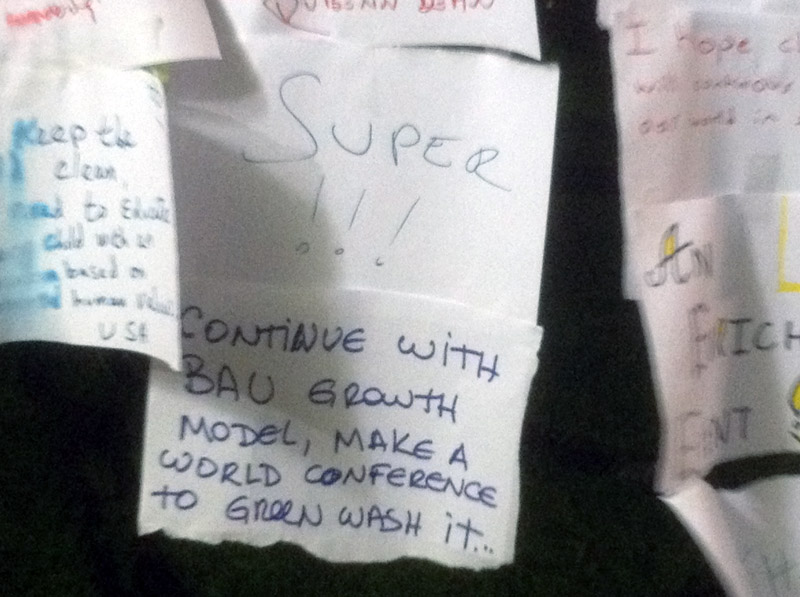

Last night disgruntled attendees wrote out their frustration. “What will our children remember about Rio+20?” asked the banner. “Super,” said one, but “greenwashing,” and “doing nothing” were more common.

Last night disgruntled attendees wrote out their frustration. “What will our children remember about Rio+20?” asked the banner. “Super,” said one, but “greenwashing,” and “doing nothing” were more common.

At lunch in the food court I head to my favorite corner of world food—sushi.

At lunch in the food court I head to my favorite corner of world food—sushi.

The line is long today, and I stand behind a young man from Timor-Leste (East Timor). Ivens speaks superb English. “It must have been all those American TV series I watched as a kid,” he laughs. What were his favorites? “Friends.”

The line is long today, and I stand behind a young man from Timor-Leste (East Timor). Ivens speaks superb English. “It must have been all those American TV series I watched as a kid,” he laughs. What were his favorites? “Friends.”

Over the next hour I get a cultural studies lesson: how his eastern end of the island was colonized by Portuguese in the fifteenth century but the other end by the Dutch in Indonesia. How East Timor sits on natural resources coveted by its neighbors. How Indonesia invaded and occupied East Timor in 1975 for more than two decades. How a journalist escaped a massacre at a cemetery in 1991, burying his film in the ground and retrieving it later by night—the very video that finally alerted the world to the horrors taking place. At the time Ivens was six and lived near the cemetery, but that morning all kinds of obstacles had prevented his father from taking him to school, so he remained safe at home.

“In East Timor we need to unify,” Ivens says with deep feeling, “so we can survive.” The many separate kingdoms and languages of his homeland have coalesced around Portuguese. “It makes sense,” he says. “Portuguese culture and language have been part of our heritage now for 500 years.” It is also unusual—embracing the colonizer’s language as a political tool. “Portuguese gives us a common identity. It is part of all of our lives.” In the past forty years East Timorese converted to Catholicism for the same reason—to build solidarity among themselves and show their collective difference from Muslim Indonesians. In all my years of studying religions, I have never heard of a whole population converting as a tool of political resistance.

When we finally go our separate ways, I have a new friend.

When we finally go our separate ways, I have a new friend.

In the afternoon I attend a panel on “Undertaking Sustainable Development, the Indigenous Peoples’ Way.” A group from one of Brazil’s indigenous peoples leads in a welcome chant and dance.

Then the richness of cultural diversity is on display as representatives from every continent offer their comments. “Our greatest wealth is nature’s diversity, and the associated cultural diversity,” says a woman from Bolivia. A Na-Dene man from northern Canada adds, “One indigenous language dies every two weeks. When a plant or animal species is in danger, everyone rushes to save it. But when a language dies, no one lifts a finger.”

Then the richness of cultural diversity is on display as representatives from every continent offer their comments. “Our greatest wealth is nature’s diversity, and the associated cultural diversity,” says a woman from Bolivia. A Na-Dene man from northern Canada adds, “One indigenous language dies every two weeks. When a plant or animal species is in danger, everyone rushes to save it. But when a language dies, no one lifts a finger.”

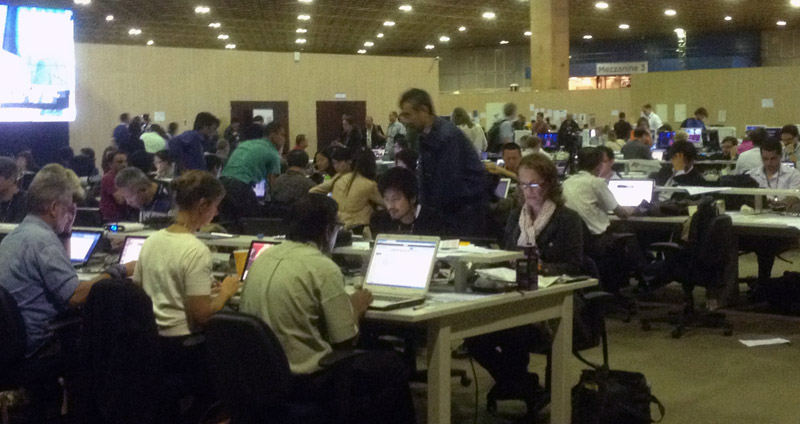

After the panel I head to the media room, and for the second time today I get lucky—I snag a chair and an outlet! A good thing too because my laptop and phone are running low, and this is the only place to plug in.

Soon it’s time to catch the bus back to Ipanema. My cohort is heading out to dinner tonight. A quick check of my email gives me the address—far across town in the other direction, a long taxi ride after the shuttle bus. Transportation at this conference is, shall we say, challenging. By the end of the day I will have spent 2 hours on buses and another hour and a half in taxis. And that’s on a day with light traffic.

Soon it’s time to catch the bus back to Ipanema. My cohort is heading out to dinner tonight. A quick check of my email gives me the address—far across town in the other direction, a long taxi ride after the shuttle bus. Transportation at this conference is, shall we say, challenging. By the end of the day I will have spent 2 hours on buses and another hour and a half in taxis. And that’s on a day with light traffic.

I’m looking forward to a delicious Brazilian dinner—maybe some fish in a tasty butter sauce, a carrot puree, a glass of wine—and samba music.

Now why didn’t I take time to learn to samba before I got here?

By the time I head to bed it’s midnight. Tomorrow it all starts again.